Prof Salim Abdool Karim Weekly COVID-19 UPDATES

In South Africa, the trends in reported cases and deaths show a small increase followed by a decline (Figure 2). But the number of reported cases remains low overall.

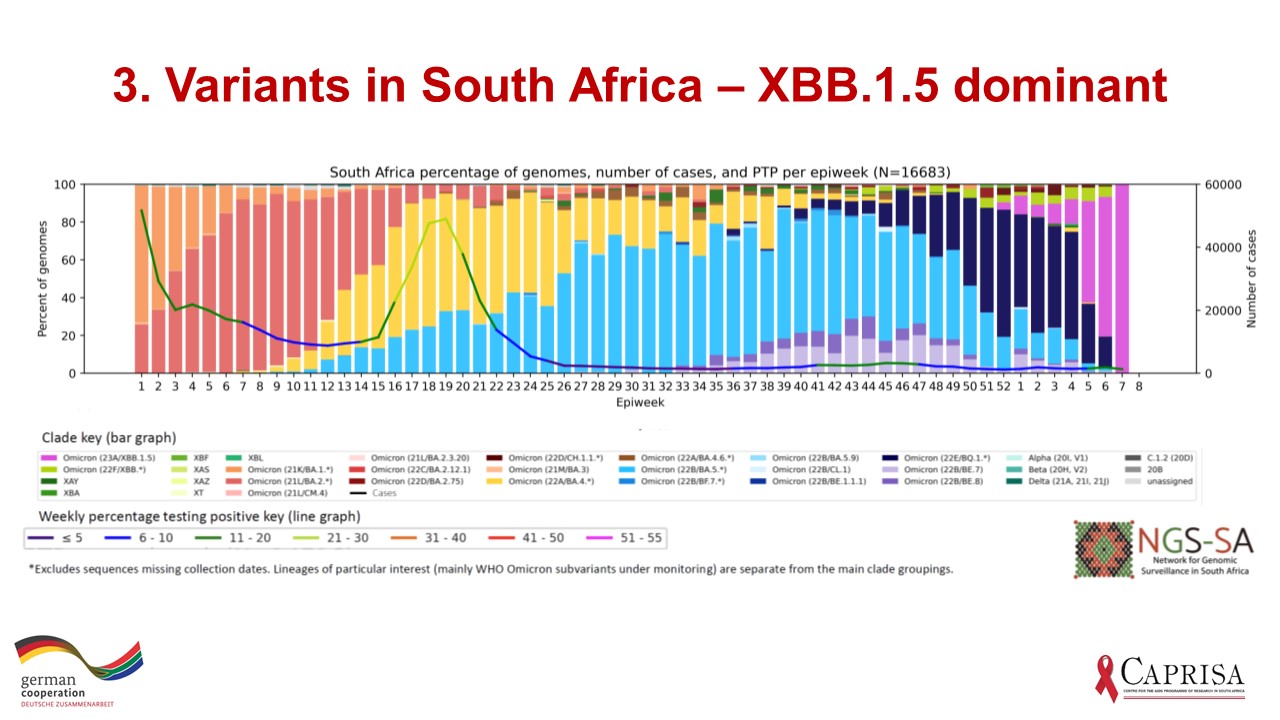

The latest distribution of viral sequences in South Africa, shows that XBB.1.5 (pink) has become dominant, replacing BQ.1 as seen in Figure 3 below, which provides a week-by-week distribution of variants in South Africa, courtesy of the Network for Genomic Surveillance in South Africa.

As I pointed out last week, this kind of change in variants would be expected to be accompanied by an increase in cases as the XBB.1.5 sub-variant transmits faster than the sub-variants it is replacing. However, reported cases show only minor increases (Figure 2). I will posit some possible reasons for why we are not seeing new waves despite the growth in XBB.1.5 cases in South Africa.

One argument is that the high levels of past infection are providing us with protection, given that South Africa’s vaccine coverage is still modest (though it is >70% in >60 years). The evidence indicates that this is only partially true. In a meta-analysis of 65 studies published in The Lancet, past infection with alpha, beta or delta did well in protecting against reinfection with any of these 3 variants. But past infection with these 3 pre-omicron variants provided very little protection against omicron – the master of immune escape. So, past infection with alpha, beta and delta cannot be the reason why South Africans are not seeing a wave of new infections due to XBB.1.5

An analysis from Qatar add the next piece in the jigsaw puzzle to help us understand the changing clinical burden of Covid-19. This case-control study confirmed the low protection against reinfection with omicron in those with past infection with alpha, beta or delta. But it showed that infection with omicron BA.1 or BA.2 is quite good (78% effective) in protecting against BA.4 or BA.5. Since South Africa had a substantial BA.1 / BA.2 wave (Figure 2), the waves due to BA.4 / BA.5 were relatively subdued and XBB.1.5 muted due to the cross-immunity within omicron. This cross-immunity among omicron sub-variants seems to be highly effective in preventing reinfection with a different omicron variant sub-lineage and may be important in new omicron sub-lineage variants not being able to spread rapidly to infect large numbers of people in South Africa and therefore it does not lead to a wave.

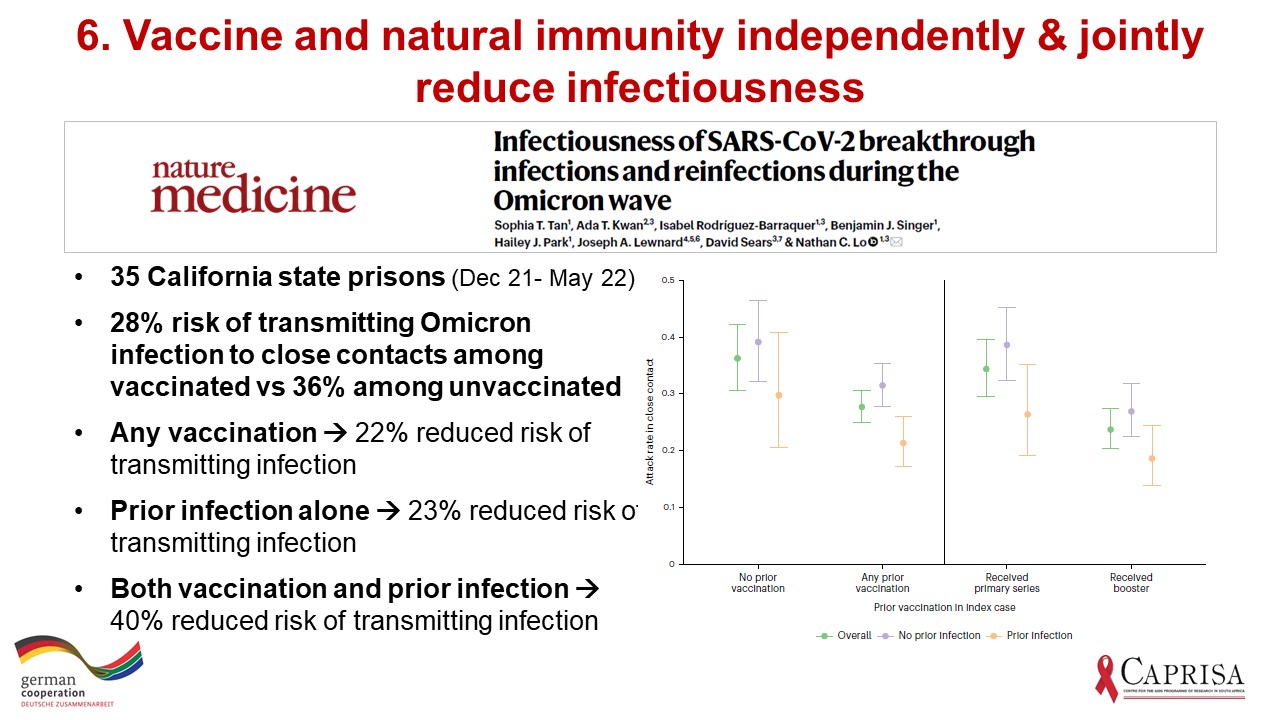

But there may be another reason why the new omicron sub-lineages are not able to spread rapidly and infect rapidly increasing numbers of people leading to a wave. Infectiousness is altered, slowing spread. In a study in Californian prisons (Figure 6), prior infection and vaccination independently dropped infectiousness by about 22% (most likely through their impact on viral load). The combination of past infection and vaccination lowered infectiousness (rate of infections in contacts) even more.

While it is likely that this combination of lowered infectiousness and cross-immunity due to omicron BA.1 or BA.2 infections has helped blunt the BA.5 wave and has kept other potential omicron waves at bay, there is the ever-present threat posed by a new variant.

How confident are we that new variants will continue to be sub-lineages of omicron and not a drastically different variant? Not confident.

As the virus spreads through the population, it reaches immune-compromised individuals leading to persistent infection, which is thought to be the main mechanism by which new variants are created. Of particular concern is the recent wave of infection in China which involved billions of viral replications, with its concomitant risk of leading to new variants. This week’s The Lancet has provided some insight into this situation (Figure 7). An analysis of close to 3000 sequences, showed no new concerning variants in Beijing. But this is only partially reassuring as the sequences were only from Beijing, which may not reflect the situation in the rest of China. More importantly, it takes many months for persistent infection to create new variants in immune-compromised people and so it is far too soon to count the chickens…

Finally, Jeff Spieler wrote to me about a New York Times article entitled, “Mask mandates did nothing.” The article is based on a Cochrane review of clinical trials investigating the impact of masks on the spread of SARS-CoV-2. I was going to explain this anomaly in today’s email but found that there was no need to as this has already been done. The various kinds of evidence for masks, the limitations of Cochrane review and why its results are misleading are well argued by “Your Local Epidemiologist” which can be read. In short, the inconclusive review concluded that there was “no evidence of a difference” – it did not find that there is “evidence of no difference.”

Have a great week.